Highlighted Stories!

"I Know The Power A Young Girl Carries In Her Heart": The Extraordinary Life Of Malala Malala Yousafzai has fought for girls' education for more than a decade. Now an Oxford graduate and at a crossroads in her own life, the 23-year-old opens up to Sirin Kale about love, family and the world she left behind, as well as her ambitious new plans for broadcasting her message. Malala Yousafzai has fought for girls' education for more than a decade. Now an Oxford graduate and at a crossroads in her own life, the 23-year-old opens up to Sirin Kale about love, family and the world she left behind, as well as her ambitious new plans for broadcasting her message.

Even the youngest Nobel Peace Prize winner in history is not immune to the occasional life freak out. "This is a question I have for myself every night," Malala Yousafzai says with a groan when I ask her where she sees herself in 10 years' time. "Lying awake in bed for hours thinking, 'What am I going to do next?'"

Malala - fresh from the previous day's Vogue shoot and still only 23 years old – goes on, "Where do I live next? Should I continue to live in the UK, or should I move to Pakistan, or another country? The second question is, who should I be living with? Should I live on my own? Should I live with my parents? I'm currently with my parents, and my parents love me, and Asian parents especially, they want their kids to be with them forever."

We sit in a quiet corner of a central London hotel. Malala's hair is loose and uncovered. Her headscarf rests in the nape of her neck. "I wear it more when I'm outside and in public," she says, seated at a quiet table, her discreet security detail sitting nearby. "At home, it's fine. If I'm with friends, it's fine." The headscarf, she explains, is about more than her Muslim faith. "It's a cultural symbol for us Pashtuns, so it represents where I come from. And Muslim girls or Pashtun girls or Pakistani girls, when we follow our traditional dress, we're considered to be oppressed, or voiceless, or living under patriarchy. I want to tell everyone that you can have your own voice within your culture, and you can have equality in your culture." |

� | � |  | |

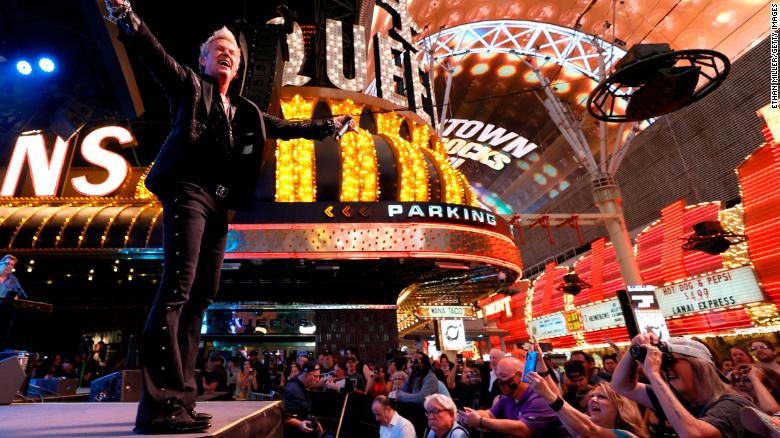

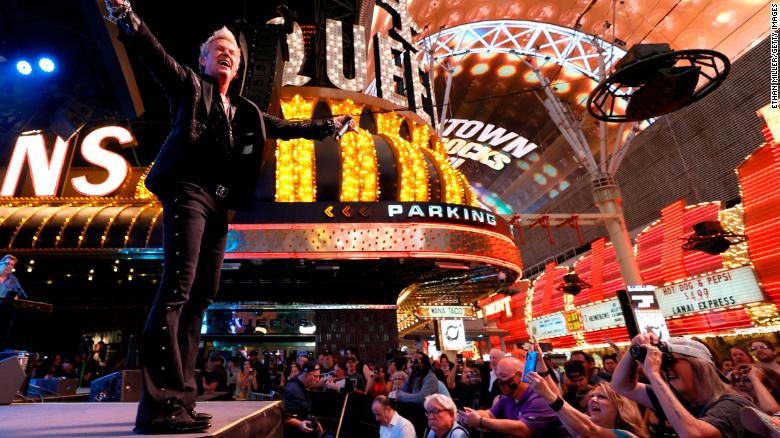

Las Vegas is ready to roll the dice on pre-pandemic normalcy Las Vegas fully reopens to 100 percent capacity Las Vegas fully reopens to 100 percent capacity

As a giant clock counted down to 12:01 Tuesday morning, crowds cheered the complete reopening of downtown Las Vegas for the first time in more than a year, with live music and no mask or social distancing required.

"This is rather a historic night in Las Vegas history," an announcer said over a loudspeaker to a mostly unmasked crowd.

And moments later, the crowd was moving to a Las Vegas band's version of a Foo Fighters' song, the first live music there in more than a year: "It's times like these, you learn to live again," the band sang. |

| � |  | |

CEO Picks - The most popular editorials that have stood the test of time! The New Productivity Revolution Innovations in biotech, energy, and space could drive the next generation of prosperity—if we let it happen. Innovations in biotech, energy, and space could drive the next generation of prosperity—if we let it happen.

Are all the significant inventions already achieved? Economist Robert Gordon identified five Great Inventions, whose discovery in the late nineteenth century powered what he deems an unrepeatable burst of economic growth between 1920 and 1970. These inventions—electrification, the internal combustion engine, chemistry, telecommunications, and indoor plumbing—were indeed far more significant than what often passes for innovation today. While some recent IT breakthroughs are important, no number of Snapchat filters can hold a candle to—well, not needing to use candles to see at night.

The phenomenon that Gordon—a careful, data-driven economist—attempts to explain is real. Economists use the concept of total factor productivity (TFP) to track the degree to which output is not attributable to observable inputs like labor-hours, capital, or education. When TFP increases, it is due to intangible factors such as innovation or better institutions. From 1920 to 1970, TFP grew at about 2 percent yearly. Since then, it has grown at less than half that rate—and in the last 15 years, it has grown at less than 0.3 percent per year, according to the San Francisco Fed's utilization-adjusted series.

Is this slowdown due to a small number of crucial past innovations running their course? Do no Great Inventions remain to be discovered? Are we now doomed to eternal stagnation? Short answer: no. All it takes to see this is a visit to the technology frontier and a little imagination. But if there is no shortage of technological possibilities, why, then, is economic growth stagnating? |

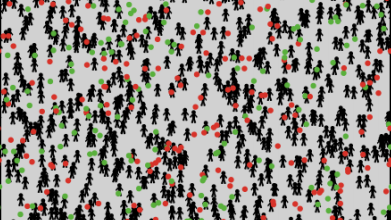

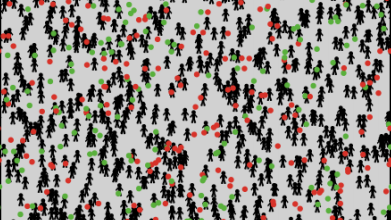

If you're so smart, why aren't you rich? Turns out it's just chance. The most successful people are not the most talented, just the luckiest, a new computer model of wealth creation confirms. Taking that into account can maximize return on many kinds of investment. The most successful people are not the most talented, just the luckiest, a new computer model of wealth creation confirms. Taking that into account can maximize return on many kinds of investment.

The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world's poorest 3.8 billion people.

This seems to occur in all societies at all scales. It is a well-studied pattern called a power law that crops up in a wide range of social phenomena. But the distribution of wealth is among the most controversial because of the issues it raises about fairness and merit. Why should so few people have so much wealth?

The conventional answer is that we live in a meritocracy in which people are rewarded for their talent, intelligence, effort, and so on. Over time, many people think, this translates into the wealth distribution that we observe, although a healthy dose of luck can play a role.

But there is a problem with this idea: while wealth distribution follows a power law, the distribution of human skills generally follows a normal distribution that is symmetric about an average value. For example, intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, follows this pattern. Average IQ is 100, but nobody has an IQ of 1,000 or 10,000.

The same is true of effort, as measured by hours worked. Some people work more hours than average and some work less, but nobody works a billion times more hours than anybody else. |

| � |  | |

In negotiation, use silence to improve outcomes for all A pause during negotiation can improve outcomes for both parties, not just the one that initiates the silence. A pause during negotiation can improve outcomes for both parties, not just the one that initiates the silence.

An online search returns hundreds of negotiation preparation checklists that all point in the same general direction: Know your strengths. Know your vulnerabilities. Clarify the interests and priorities of the other party. Determine your best alternative to a negotiated agreement. And so on.

Rarely, though, do these checklists encourage silence.

But new research led byJared Curhan, Gordon Kaufman Professor and associate professor of work and organization studies at MIT Sloan, suggests that pausing during negotiations can improve outcomes — and not only for the person who initiates the silence, but for both parties in the negotiation.

"When put on the spot to respond to a tricky question or comment, negotiators often feel as though they must reply immediately so as not to appear weak or disrupt the flow of the negotiation," said Curhan, who collaborated with Jennifer R. Overbeck of Melbourne Business School, Yeri Cho of the University of La Verne, Teng Zhang of Penn State Harrisburg, and Yu Yang of ShanghaiTech University.

"Our research suggests that pausing silently can be a simple yet very effective tool to help negotiators shift from fixed-pie thinking to a more reflective state of mind," said Curhan. "This, in turn, leads to the recognition of golden opportunities to expand the proverbial pie and create value for both sides." |

| � |  | |

How to Talk to an Employee Who Isn't Meeting Their Goals Having to tell someone that they're not meeting their work standards can get awkward fast. Luckily, simply asking them to evaluate themselves can do a lot of the work for you. If they can spot the problems on their own, it saves you a lot of trouble. If not, make sure that your goals and visions are aligned. State the non-negotiables and how it can help them further their career. Be clear about your employee's failings by describing specific examples and behaviors you observed, giving them guidelines about how they can get back on track. Ask them to create an improvement plan and then review together, filling any gaps they might have missed, setting deadlines, and explaining repercussions if the goals are not met. Confrontation about shortcomings is much easier when it's done with a shared vision, clear expectations, and a plan to move forward. Having to tell someone that they're not meeting their work standards can get awkward fast. Luckily, simply asking them to evaluate themselves can do a lot of the work for you. If they can spot the problems on their own, it saves you a lot of trouble. If not, make sure that your goals and visions are aligned. State the non-negotiables and how it can help them further their career. Be clear about your employee's failings by describing specific examples and behaviors you observed, giving them guidelines about how they can get back on track. Ask them to create an improvement plan and then review together, filling any gaps they might have missed, setting deadlines, and explaining repercussions if the goals are not met. Confrontation about shortcomings is much easier when it's done with a shared vision, clear expectations, and a plan to move forward. |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment